The Tripartite Framework for Effective Fiduciary Monitoring

Published on: Mon Apr 22 2024 by Ivar Strand

In international development and post-conflict stabilization, the monitoring of projects is a fundamental requirement for accountability. Financing agencies have a fiduciary duty to ensure funds are used effectively and for their intended purpose. However, the conventional approach to monitoring often creates friction between the parties it is meant to align. It positions the monitor as an external auditor, fostering an adversarial relationship with the implementing agency that ultimately undermines project success.

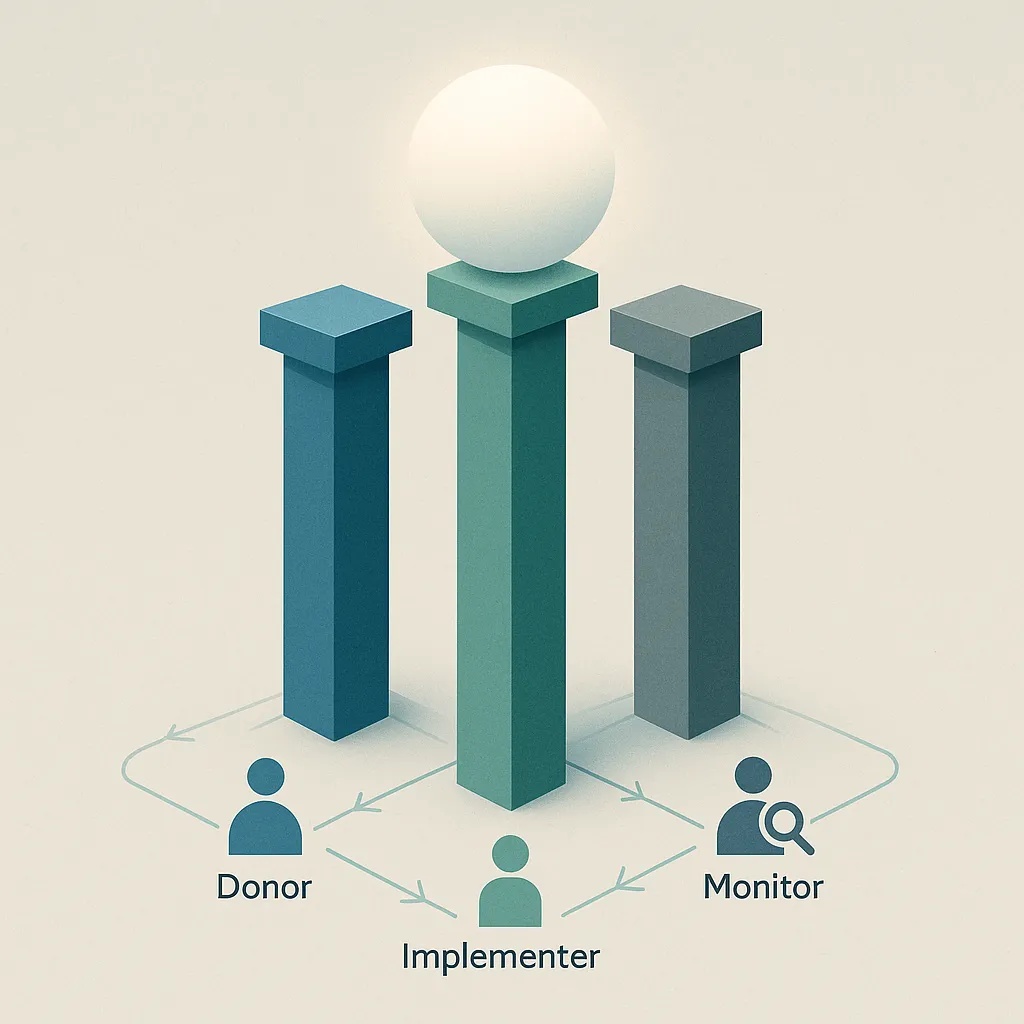

At Abyrint, we have found that effective monitoring is not an audit function performed on a project, but a management tool used by a project. This requires a shift from a bilateral reporting line to a collaborative, tripartite relationship between the donor, the implementer, and the monitor. In this paper, we outline the pillars of this collaborative model.

1. The Flawed Model: Monitoring as External Audit

The archetypical monitoring arrangement involves a donor contracting a Third-Party Monitor (TPM) to independently verify the activities of an Implementing Agency. In this structure, the TPM’s primary reporting line is to the donor. The implementer becomes the subject of scrutiny, not a partner in the process.

This model is suboptimal for several reasons:

- It creates information asymmetry. Fearing penalties, the implementing agency has an incentive to hide challenges and report only successes. The monitor is forced into an investigative role to uncover the ground truth, which destroys trust.

- It fosters a compliance mindset. The implementer’s goal shifts from achieving project outcomes to satisfying the monitor’s checklist. This discourages innovation and adaptive management.

- It delays corrective action. Findings are reported up to the donor, who then must decide on a course of action to direct back down to the implementer. This feedback loop can take weeks or months, during which time a solvable problem can become critical.

- It misaligns interests. The model inadvertently pits the monitor and the implementer against each other, when they should be allies in achieving the project’s goals.

2. A New Framework: The Tripartite Collaborative Model

A more functional approach establishes a formal or informal tripartite agreement where all three parties share responsibility for using monitoring data to improve performance. The central idea is to realign monitoring as a tool for learning and real-time decision-making.

This structure reframes the roles of each actor:

- The Donor: Sets the high-level strategic objectives and fiduciary red lines. The donor delegates the operational oversight to the collaborative process, stepping in only when strategic adjustments are needed.

- The Implementing Agency: Is the primary consumer of monitoring data. The agency is empowered and expected to use the findings to adjust its approach, solve problems, and report on its corrective actions.

- The Third-Party Monitor: Acts as an objective facilitator and data provider to both parties. The monitor’s role is to present a shared, factual basis for discussion, not to pass judgment.

This relationship ensures that information flows freely between all parties, creating a unified team focused on a single set of project goals.

Exhibit A: Contrasting Monitoring Models (A conceptual diagram would be placed here, illustrating the linear, fractured flow of the audit model versus the triangular, collaborative flow of the tripartite model.)

3. The Three Pillars in Practice

Implementing this collaborative model depends on three practical commitments.

Pillar 1. Shared Objectives and Unified Reporting The foundation of the tripartite model is a single, undisputed source of information. This begins with a shared understanding of project objectives and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Subsequently, all monitoring reports, field data, and findings from the TPM must be delivered simultaneously to the implementing agency and the donor. There can be no “secret” back-channel reports to the donor. This practice eliminates information asymmetry and ensures all discussions are based on a common set of facts.

Pillar 2. Regular, Structured Dialogue Collaboration requires a forum. The tripartite agreement should mandate regular meetings—typically monthly or quarterly—attended by representatives from all three parties. The purpose of these meetings is not for the monitor to “present findings” to the other two, but for the collective to:

- Review progress against shared KPIs.

- Discuss operational challenges identified by the monitor.

- Agree on specific, actionable steps for the implementing agency to take.

- Document decisions and establish a timeline for follow-up.

The focus of the dialogue must be forward-looking: “Given this information, what do we do next?”

Pillar 3. A Mandate for Corrective Action The tripartite model is only effective if the implementing agency is empowered to act. The donor must provide the implementer with a clear mandate and the delegated authority to make operational adjustments based on monitoring data, without seeking prior approval for every minor deviation. The burden of proof shifts. The implementer is not expected to be perfect, but it is expected to be responsive. The monitor’s role then expands to include tracking whether the agreed-upon corrective actions have been implemented, creating a closed feedback loop.

From Friction to Function

Viewing project monitoring as an external audit is a deeply ingrained practice, but it is one that consistently produces friction and sub-optimal results. It prioritizes accountability in form over accountability in function.

By restructuring the relationship around a collaborative, tripartite framework, stakeholders can transform monitoring from a source of conflict into a powerful management tool. This model fosters transparency, enables adaptive management, and aligns the interests of the donor, implementer, and monitor toward the only goal that matters: achieving better project outcomes. The approach is not complex, but it does require a deliberate shift in mindset from all parties involved.