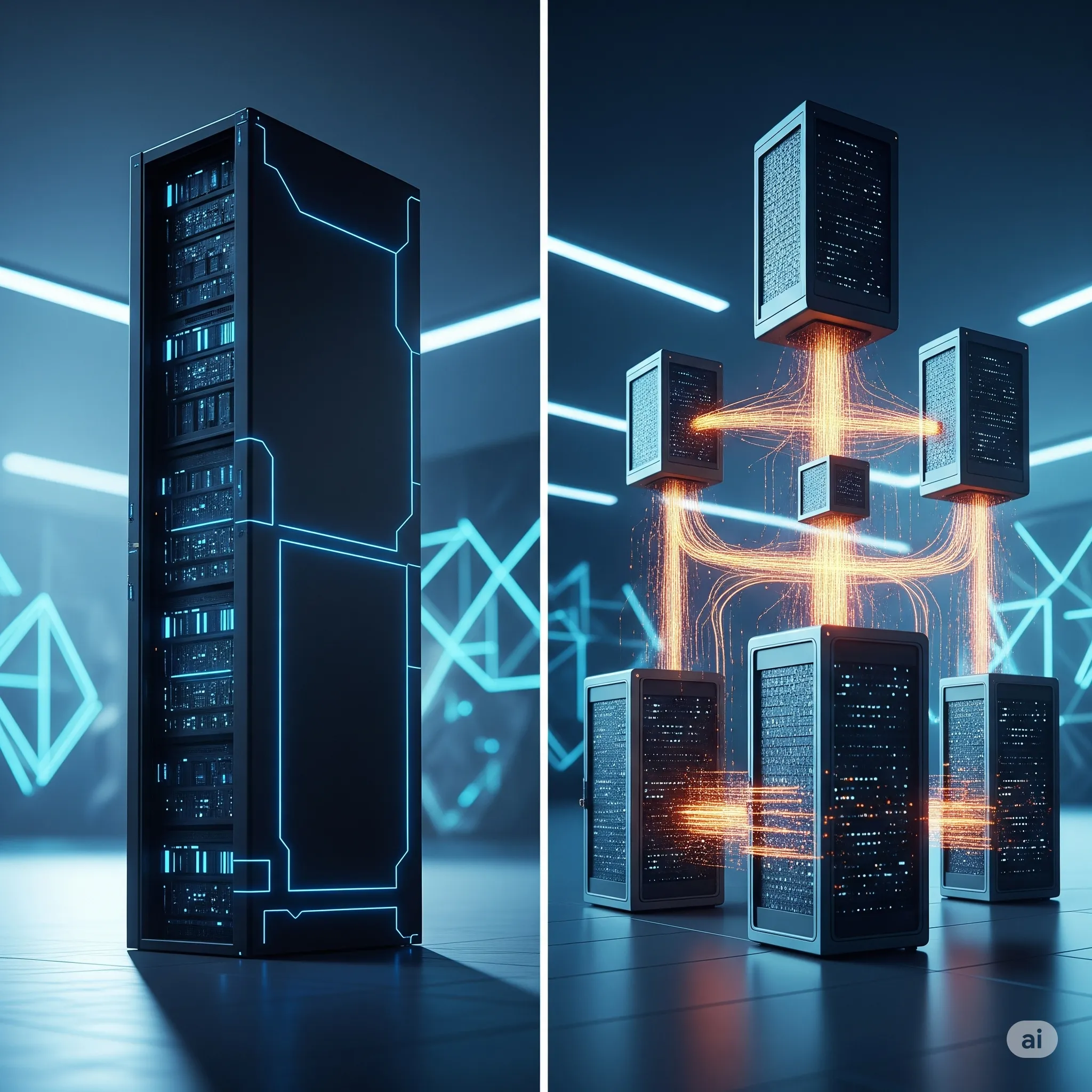

Federated vs. Monolithic Architectures - Core Choices in Public Finance Systems

Published on: Tue Jun 25 2024 by Ivar Strand

A recurring strategic challenge we observe in public finance modernization is a fundamental architectural dilemma. As government agencies mature and their programmatic needs grow more complex, a central question arises: should the state expand its core Financial Management Information System (FMIS) into an all-encompassing monolith, or should it foster a federation of specialized systems interconnected through a common standard?

This is not merely a technical question; it is a core question of governance. The choice determines the balance between central fiscal control and devolved operational agility. While the instinct for a single, centralized system is strong, our analysis suggests that a decentralized, federated model is often the more resilient and sustainable architecture for a modern state.

The Monolithic Approach: The Promise of Centralized Control

The first and historically most common trajectory is to expand the existing central FMIS to serve all government entities. This approach involves extending the national chart of accounts to capture the granular detail of every agency and onboarding a vast and diverse user base onto a single platform.

The theoretical advantages of this model are clear and align with traditional principles of public finance:

- Unified Data and Control. A single system creates one source of truth for all financial data, which simplifies national budget consolidation, expenditure tracking, and macro-fiscal analysis.

- Enforced Standardization. It mandates uniform accounting standards and procedures across the entire government apparatus, ensuring a consistent application of the de jure rules.

- Simplified Reporting. The ability to generate consolidated reports for legislative bodies and international partners directly from one system is a significant operational advantage.

The Practical Limitations of the Monolith

While compelling in theory, this approach is fraught with practical challenges, particularly in developing state contexts where the central FMIS may itself have limitations in design or access.

- Inherent Rigidity. Monolithic systems, often built on older technological foundations, are not designed for the level of flexibility required by diverse, specialized agencies. The unique programmatic needs of a ministry of health, for example, are fundamentally different from those of a ministry of public works. Forcing both onto a single, rigid platform creates inefficiency and encourages the use of informal “shadow systems.”

- A Systemic Single Point of Failure. A major technical failure, cyber-attack, or vendor issue affecting the central monolith can disrupt the financial operations of the entire state apparatus simultaneously.

- Prohibitive Implementation Cost. The technical, financial, and political capital required to successfully manage a massive, multi-year project to expand a central FMIS across all of government is immense. Case studies from numerous countries have documented the significant challenges of these large-scale implementations.

An Alternative Trajectory: The Federated, API-Driven Model

An alternative and increasingly favored approach is a decentralized, or federated, architecture. In this model, the central treasury shifts its role from being the universal service provider to being the central standard-setter and data hub.

Individual agencies are empowered to procure or develop financial systems that are fit for their specific purpose. These systems are then required to connect to the central treasury system through a set of secure, standardized, and well-documented Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). This API-first strategy offers several advantages:

- Flexibility and Agility. Agencies can adopt solutions that meet their specific operational needs, fostering greater efficiency and allowing them to adapt more quickly to changing programmatic requirements.

- Enhanced Resilience. The impact of a system failure is localized to a single agency, preventing a catastrophic, government-wide disruption.

- Sustainable Scalability. The architecture can evolve more gracefully. New agencies and new digital services can be added to the ecosystem without requiring a complete overhaul of the central system.

- Mitigation of Vendor Lock-in. A federated model avoids the significant risk of a single technology vendor controlling the entire government’s financial technology stack.

This model is the practical application of the modern Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) concept, which emphasizes modularity and interoperability as the foundation for resilient and effective digital governance.

Conclusion: The Prevailing Trend Towards Modularity

While the optimal solution is always context-dependent, the global trend, supported by the analysis of institutions like the World Bank and IMF, is a clear movement away from the monolithic paradigm. At a certain point of complexity, a decentralized architecture is not just more manageable; it is more robust.

The federated approach allows a government to achieve its central fiduciary oversight objectives by mandating compliance with its data and API standards, ensuring that while the systems are many, the financial language they speak is one. For a state navigating the complexities of modernization, this represents a more mature, resilient, and ultimately more pragmatic path forward.