Remote Fiduciary Oversight in Non-Permissive Security Environments

Published on: Sun Jun 01 2025 by Ivar Strand

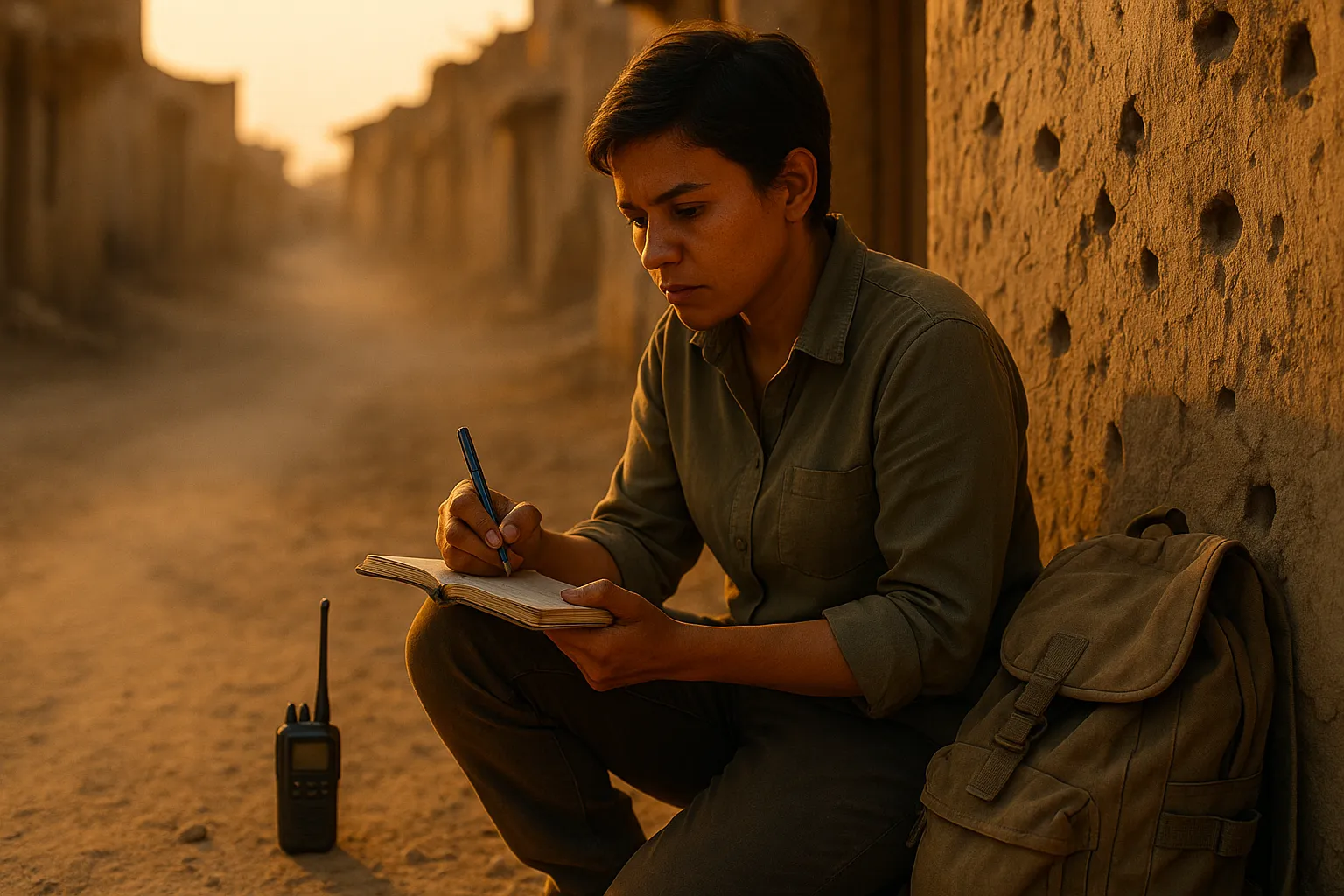

Eyes and Ears on the Ground: The Unique Challenges of Monitoring in Conflict Zones

Monitoring development and stabilisation programmes is a cornerstone of effective intervention. It provides the data needed for accountability, learning, and adaptive management. However, applying standard Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) frameworks to Fragile and Conflict-Affected (FCV) situations is a frequent and critical error. The assumptions of stability, access, and reliable data on which most results-based frameworks depend do not hold.

In this paper, we discuss the unique challenges of monitoring in these environments. We argue that effective monitoring in FCV settings is not a technical exercise in data collection, but an analytical practice of sense-making that must be directly integrated with security and political analysis.

The Mismatch of Standard M&E in FCV Contexts

The archetypical M&E framework, built on a logical model of inputs, outputs, and outcomes, presumes a degree of predictability. It assumes that a programme can be implemented more or less as planned and that the primary challenge is to measure progress against pre-defined indicators.

This model breaks down in conflict environments. The context is defined by non-linear dynamics, exogenous shocks, and the consistent presence of actors who may actively work against a programme’s objectives. A project plan is less a roadmap and more a statement of intent, subject to constant revision. Thus, a monitoring system focused solely on verifying progress against a static plan becomes obsolete quickly.

The Core Challenges

At Abyrint, we have worked on programme design and oversight in numerous conflict-affected regions. We find the challenges to effective monitoring consistently fall into three main categories.

1. The Challenge of Security and Physical Access The most immediate challenge is physical access. Programme sites may be intermittently or permanently inaccessible due to active hostilities, shifting frontlines, checkpoints, or generalized criminality.

- Direct Observation is Limited: The ability for programme staff—particularly international staff—to conduct site visits and verify activities firsthand is severely constrained.

- Operational Pauses: Entire programmes may be forced to pause for extended periods, making trend analysis based on regular reporting intervals difficult.

- Security Risk: The primary operational concern is managing security risk for staff and partners. This operational tempo, dictated by security protocols rather than programmatic needs, is a fundamental reality. Describing this environment as merely “challenging” is an understatement; it may include direct threats to personnel.

2. The Challenge of Political and Social Complexity Monitoring in FCV settings is not a politically neutral act. The collection and perceived use of information can have significant, unintended consequences.

- Factional Instrumentalization: Information can be used by local power brokers to target rivals or extract resources. An enumerator asking questions about aid distribution can inadvertently create new tensions.

- Doing Harm: Identifying beneficiaries or local partners in a report could expose them to risk. The principle of “do no harm” must govern all data handling protocols.

- Information as an Asset: In conflict, information is a valuable asset. Local actors may deliberately provide misleading data to manipulate programme resources in their favour, creating significant fiduciary risk.

3. The Challenge of Data Reliability Even when access is possible, the integrity of the data collected is often questionable. Standard survey and data collection methods face immense hurdles.

- Lack of Baseline Data: Reliable baseline data (e.g., census data, economic indicators) is often non-existent or decades old, making it difficult to measure change over time.

- Displaced Populations: Population movements make sampling for surveys a highly complex task.

- Respondent Bias: Fear, a desire to provide a “correct” answer to secure aid, or distrust of outsiders can heavily skew responses in qualitative and quantitative data collection.

A More Viable Framework for FCV Monitoring

A pragmatic approach is required—one that accepts these constraints and is designed for them. It prioritizes usefulness and risk management over methodological purity. We suggest a framework built on four key pillars.

Exhibit A: A Triangulation Model for FCV Monitoring

To compensate for the unreliability of any single data source, we rely on a structured triangulation of information from three distinct channels:

- Remote Monitoring: Using satellite imagery, social media analysis, and other technological tools to verify activities (e.g., confirming a school building is still standing).

- Local Network Intelligence: Systematically gathering qualitative insights from a trusted, well-managed network of local partners and community contacts.

- Limited Direct Observation: Conducting targeted, high-impact field visits when and where security permits, focusing on verification and problem-solving, not routine data collection.

The Four Pillars of the Framework:

-

Redefine the Purpose: The primary purpose of monitoring in FCV settings is not accountability against a static plan. It is to inform adaptive management. The key question is not “Did we do what we said we would do?” but rather, “Given the changes in the context, is what we are doing still the right thing to do?”

-

Employ Triangulation: Relying on a single source of information is untenable. The key is to systematically cross-reference and triangulate data from the three channels described in Exhibit A. If remote sensing shows a road is clear, local contacts report normal commercial activity, and a partner confirms a delivery, we can have a high degree of confidence.

-

Integrate Security with Programmatic Monitoring: These functions cannot be siloed. A security report about a new checkpoint is a critical piece of programmatic data; it directly impacts logistics and delivery timelines. Likewise, a programme report about community tensions is vital security intelligence. This requires integrated teams and reporting structures.

-

Uphold an Uncompromising Duty of Care: The safety of staff, partners, and beneficiaries must be the paramount consideration. This means that data collection protocols must include a risk assessment, and that the decision to not collect certain data due to risk is a valid and necessary programmatic choice.

From Data Collection to Sense-Making

Monitoring in conflict zones is not a straightforward technical exercise. Attempting to impose rigid, conventional M&E systems is ineffective and can create unacceptable risk.

The key idea is to move beyond mere data collection toward a disciplined process of sense-making. This requires a flexible and resilient framework that triangulates information from multiple sources, fully integrates security analysis, and empowers managers to make judgements in ambiguous, high-stakes environments. Ultimately, the value of a monitoring system in a conflict zone is measured not by the volume of its data, but by its ability to inform sound decision-making under pressure.